SUSANNE K. MADER

SOHO

10.09 - 23.10.2022

“The more freely the abstract in the form appears, the purer and thus more elementary it sounds. […] There is no ‘must’ in art; art is eternally free. For the word ‘must’ art flees like day for night.”¹

The quote is taken from the iconic essay “On the Spiritual in Art,” in which artist and theorist Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) emphasizes the importance of forms having a certain freedom, and that this has an impact on the quality of the forms. In other words, Kandinsky bases his work on the premise that free art is a prerequisite for formal quality, which in turn leads to the richest possible resonance between the parts involved.

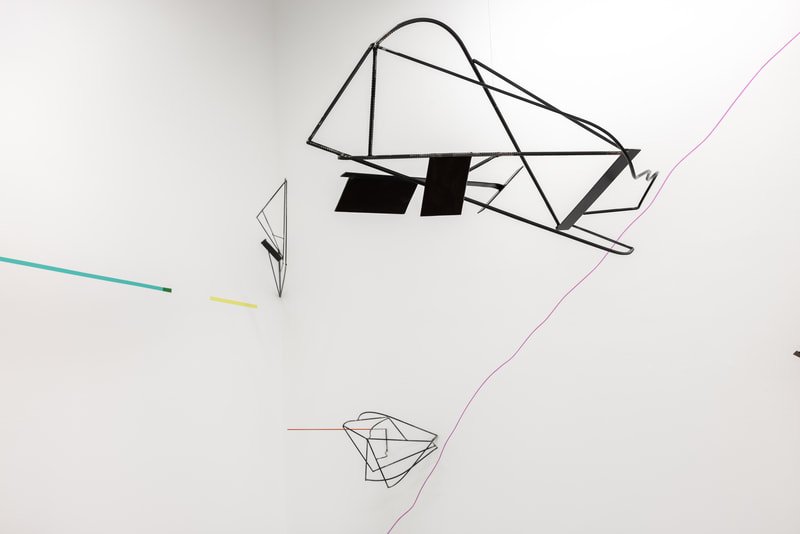

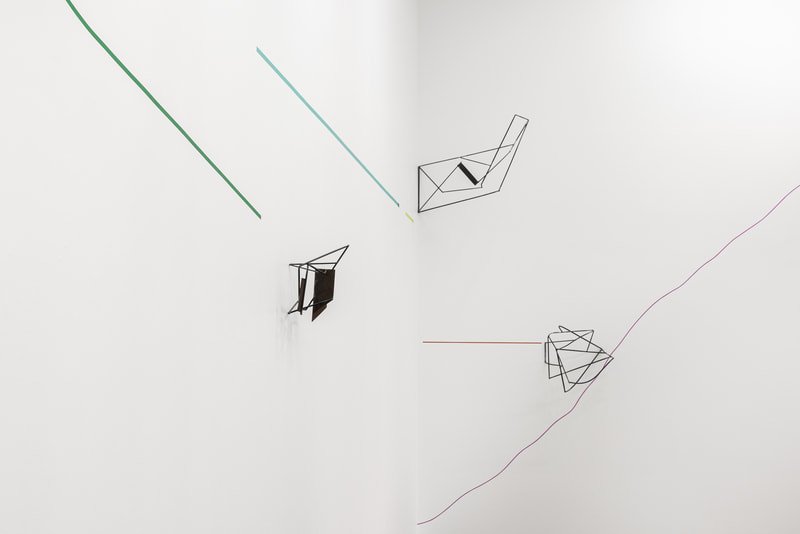

IN Trafo Kunsthall A series of welded steel sculptures have taken over the hall, where they have found their places in the corners, along the walls, standing on the floor, and floating airily from the ceiling. Assembled from slender steel pieces without solid surfaces, the sculptures appear primarily abstract, but also open – as if they are trying to outline the air space they occupy. Individually, the sculptures consist of crisscrossing lines, which, due to their appearance, almost demand to be seen from different angles. Considered as a whole, they form an ensemble that can hardly be described as anything other than dynamic and free.

The ensemble also includes a number of murals, although not of the towering variety often associated with the format. Here, we are talking about fields of color so thin that one might be led to believe that a simple brush has been used. “Line” or “stroke” seems to be a more precise description, but for the sake of clarification: Executed directly on the wall with masking tape, acrylic paint and meticulous precision, this is (also) a mural. What is striking, however, is their appearance: Directional elements that are not in danger of running out of energy because they are stretched too far, held in a palette that creates depth and resonance in the encounter with both each other and the black steel.

Despite a relatively airy first impression, it is a sometimes challenging perspective that the viewer is encouraged to adopt. SOHO requires an active gaze, where one has to lift one's gaze to capture both the whole and all its components – from sculpture to sculpture, via line to line, interrupted only by larger and smaller spaces as careful breathing spaces along the way. None of the parts physically connect to each other, and any connections between them are only suggested through placement. Lines in the sculptures are replicated in the murals, or perhaps the opposite is true. Low-key but articulate murals extend and accentuate the welded forms.

Despite the fact that SOHO consists of a number of individual works, it is equally natural to also consider it as a total installation in which melodic forms together constitute a symphonic form – to use Kandinsky's terms.² As far as compositions are concerned, according to Kandinsky there are only two main forms: 1) The melodic form, which is the simple composition and subordinate to a clearly prominent form, and 2) the symphonic form, which constitutes the complex composition, consisting of several forms subordinate to a main form.³

Art history is full of examples of how a good composition is the result of mathematical calculations, but in SOHO there are no mathematical calculations. Without a predetermined plan, the exhibition has been created on site, and as a viewer one can sense the immediate lightness that can only come from the unplanned. With an intuitive approach and a sensitivity to the objects’ need for space to unfold while also finding their place in space, SOHO has grown – part by part, sculpture by sculpture, mural by mural – all the while keeping balance and mutual logic between the parts as the goal for the eye.

Welded lines intersect painted lines, provided that perspective allows, steel plates find their counterpart in color fields, undulating steel blanks are replicated by undulating lines. The free approach to the process and the experience of the immediacy that follows are balanced by the relatively strict precision inherent in the time-consuming technical execution.

Painting has long played a central role in Susanne K. Mader's artistry, but this time the painterly aspect is present only through the sparse but diametrically expressive murals, and with the carefully selected color palette. With their unpretentious appearance, they can be experienced as subordinate to the welded sculptures. However, they are essential for the sound of the composition, and consequently the balance of the whole. In many ways, the exhibition appears in Trafo Kunsthall as a concentrate of Susanne K. Mader's practice, where the melodic parts find their role in the symphonic whole. The whole appears articulate and clear, in an enveloping but not suffocating visual sound world.

Text by Monica Holmen, curator at Nitja Center for Contemporary Art.

¹ Wassily Kandinsky, On the Spiritual in Art. Pax Forlag: Oslo, 2001. pp. 74–75.

² Ibid., p. 143.

³ Ibid., p. 143.

Susanne Kathlen Mader (b. 1964, Germany) has lived and worked in Norway since 1998 and is educated at the University of Arts, Braunschweig, Germany. Mader has an extensive exhibition activity, which includes solo exhibitions at Bærum Kunsthall, Kunstnerforbundet, LNM, Nordnorsk Kunstnersenter and Oslo Kunstforening. Mader has worked extensively with art in public spaces and is represented in several major collections, including the work Colour meets line from Risenga ungdomsskole in Asker, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Defence, the Norwegian Health Inspection and the Oslo University Art Collection.